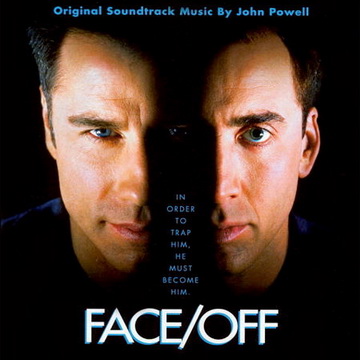

John Powell used to be one of the members of Hans Zimmer's Media Ventures group and assisted on a number of big productions. As the years past, the composer grabbed the attention of filmmakers and film score fans by taking a slightly different route, which resulted in great scores like Face/Off, the Bourne-films, Robots or X-Men: The Last Stand. We had the chance to talk to the composer about the wide array of projects he had done and talk about his latest score, written for the animated feature Happy Feet.

First, I'd like to ask you about an event that took place last month – The World Soundtrack Awards in Ghent. How do you feel it went?

It went very well – I enjoyed myself and the orchestra played very well. It was very nice to meet other composers there as you never normally get to meet them because it's a very solitary job. Gustavo Santaolalla was there and he played something from Brokeback Mountain and sang a song just on his guitar. It was lovely, it was really nice. They're very, very kind there and so respectful of film music so it's a wonderful experience for a composer.

You had roughly 30 minutes of music played. How did you select what to represent from your body of work?

You had roughly 30 minutes of music played. How did you select what to represent from your body of work?The tricky thing is a lot of the music I've written might not be very well represented by just playing it live. A lot of it uses electronics and a lot of ethnic percussion and ethnic instruments, so it was difficult. I had to be practical about which pieces would work for a standard symphony orchestra with some adaptation. So we did do re-orchestration and adaptation of some pieces but I needed some things that I thought would work well for the orchestra and the players and the environment.

I'd like to make this a bit of a retrospective interview, so I'd like to begin at your roots and your early musical career. What was your first experience with music, how did you begin this career?

My first experience of music was through my father who was a tuba player with Thomas Beecham in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and so I just grew up with music all around me. Probably my first significant musical experience was listening to the Mendelson Violin Concerto and humming it all the way home from a rehearsal with my father, and asking for a violin. So at age 7 I started playing the violin.

So you've come from a classical background then?

Until I was a teenager!

Later on you joined Media Arts Group and you worked at Air-Edel in London. What can you tell us about this? What did you compose for?

With Media Arts Group I was with a friend (Gavin Greenaway) whom I had met at Trinity College of Music. We were going out and doing other things including writing films for students at the International Film School, writing pieces for choreography students at the Central School of Dance and one of the things was that we met up with an artist by the name of Michael Petry. He was part of Media Arts Group, which is a performance art group, so Gavin and I started to involve ourselves with them, writing music for the pieces. They eventually split up but Michael and Gavin and this other composer and I carried on working together, and we did a lot of mixed media art pieces, whereby there would be music as part of the piece, or video installation as part of the piece, and we could compose the music for that. Then later on I joined Air-Edel which is a music company that has lots of composers that write music for adverts and TV, and they took me on and I started to work in advertising. I think it's a very useful type of craft study as you get to write lots of different styles and you have to do it under extreme pressure. You have to deal with people asking you to write music, but they don't really know what they want a lot of the time and it was all very good preparation for working in film.

I heard you wrote an opera called An Englishman, An Irishman and a Frenchman. What was the story behind this?

That was a piece that was commissioned by the National Gallery of Germany in Bonn. They have a 300 seat hall where they put on pieces and they had been working with Michael Petry. They had taken some of the installation art he had created with Gavin and I, and I think it was just a drunken night he said "I have an idea for a short opera, so why don't we do it? The guys at Bonn say they'll help us to fund it." So he wrote this libretto called "An Englishman, An Irishman and a Frenchman" and it is basically a conversation between three artists that were English, Irish and French. They are sitting in a salon in heaven discussing their life and the things they enjoy and it's 70 minutes. It had 4 main characters, this little cast of about 12 female singers and a small orchestra of about 10. We performed it for 2 nights in Bonn and it was significant in the sense that it was the largest thing that Gavin and I had written and also significant for me that I enjoyed it so much more than I thought I would, and so much more than what I was doing at the time which was music for advertising and I really thought it was the time to move on. So that piece gave me the incentive to move to Hollywood.

Well you moved to America and joined the group Media Ventures. What can you tell me about your early years here, before writing your breakthrough score to Face/Off?

Well you moved to America and joined the group Media Ventures. What can you tell me about your early years here, before writing your breakthrough score to Face/Off?I really just decided to go to Los Angeles and maybe pick up some work. I knew Hans Zimmer from London and he said to me several years beforehand "Why don't you come over? We're always looking for young talent." It took me a few years to go because I didn't really feel I was ready for it but after the opera I really felt that I would go, and I took a very nice apartment overlooking Venice Pier and I spent the first 3 months in Los Angeles really just having a very nice time – it was really like a holiday! I knew that I could live here for a year with no work and I would be fine because I'd made money in advertising, but I continued doing a little bit of work for Europe in advertising, yet at the same time Hans did call me and started to feed me little things to do. For instance, I worked very early on some of the song arrangements for Prince of Egypt and those kind of things snowballed until eventually Hans was called about this film called Face/Off and he said he couldn't do it but he knew a "kid" who can (that was me). He gave them a guarantee that was if they let me write demos for some footage and if they liked it they would hire me, but if everything went wrong than he would pick up the pieces and make sure the score got finished and was good. So it was an incredible generosity on Hans's part that got me into that film.

Well it's amazing that you got such a big job after such a short time. I think it's one of the best major debut scores I've heard. Anyway, after this you had a string of animation projects. Did you choose to do animation deliberately or did it just happen like that?

I've always loved animation so I'm a big fan of the genre along with the music for animation, so it was just pure, great, wonderful luck that it happened to be that Hans was involved with this new forming company, DreamWorks Animation. Obviously I was working there on their first project, The Prince of Egypt, and so was Harry Gregson-Williams. He did some additional score for Hans when it was scoring and I did a lot of song arrangements and things. So Jeffrey Katzenberg came into contact with both Harry and I and came up with the idea that for AntZ perhaps both of us together could try writing the score and we did some demos and they liked it and they hired us and this rest is, you know...history.

Apart from AntZ, you also worked with Harry on Shrek as well (at DreamWorks). How did you and Harry work together? What was your method in this duel concept?

Apart from AntZ, you also worked with Harry on Shrek as well (at DreamWorks). How did you and Harry work together? What was your method in this duel concept?Well with all three films, Chicken Run, Shrek and AntZ what happened was Harry and I would meet and would spend hours together and basically just write themes together, write ideas, bring ideas to each other and sort of bounce them off each other. I had always done this with Gavin and I was quite used to writing in collaboration with another composer. I didn't really know that it's quite unusual. I always thought that people did it because songwriters do it and it made perfect sense to me. So we'd have fun, try things out and try these ideas on the filmmakers. Once we had a structure of an idea or an idea of scenes, we would each take the idea and start to apply it to different sections of the movie. So Harry might do an opening sequence and then I would then head into one of the big action sequences or something like that. We would split up the work and then take those themes and start to develop them throughout the movie. There was still a lot of interaction here, as if I was working on a cue, Harry might come into my room and have a look and we would talk about it and see if there was any help we could give each other. It was an interactive process but obviously the work was split up between the two of us. The cues were somewhat separate but ultimately we were using the material we had developed together.

How would you describe the difference between composing for animation rather than a live action feature?

Ultimately, there really shouldn't be any difference. The same process of storytelling is going on and it's often better in animation than in live action. So really you're doing the same kind of job. The only difference that is stylistically all the ones I've done are basically comedies with some action. So you're writing comedy music, which tends to have a lightheartedness to it. With animation as well, there's a tradition of writing a bit closer to the movement in picture. A lot more detail really goes into it because the nature of the way animation is made. The filmmakers are more focused on details as well, so they like to be right in there looking at every note you write almost. It can be more time consuming but it's a lot of fun, partly because of the films and partly because of the process.

Were you approached for "Shrek 2"? I understand this was just Harry.

Yes, that was just Harry. I loved working with Harry, I think we'd do it again in the future, but ultimately it was dangerous for us. In Hollywood it's the easiest thing to be pigeon-holed and if we did too many films together then we would always have to do work together. You'd be amazed at how many people, even after Shrek couldn't consider that Harry and I were capable of writing scores on our own. So it was important that we both worked on separate movies and I think it might happen again in the future if Harry wanted it, but it's been much better for Harry and I to work apart, doing our own films, and also developing our own styles and our own ways of working, otherwise we would have just been a duo and it would have been impossible to get work separately.

Well you proved them wrong as you've both written magnificent scores individually as well. Endurance was the story of Olympic runner Halie Gebrselassie. The score contains lots of ethical influences. What kind of research do you do when venturing into world music?

Well you proved them wrong as you've both written magnificent scores individually as well. Endurance was the story of Olympic runner Halie Gebrselassie. The score contains lots of ethical influences. What kind of research do you do when venturing into world music?Well on that film, there were a mixture of things that happened. Terry Malick, who was the producer on the film, was very involved in the music. He had already done a lot of research on Ethiopian music and he had a lot of CDs. Unfortunately the problem with a lot of the music they had was that they couldn't make it work in the film. I actually took quite a few pieces from CD and embroidered them with what I like to think of as a "western bridge" so that people could understand what was going on musically by hearing something else going on at the same time, something that perhaps supported the idea a little more obviously for a western style of music. Some music was also recorded there. They had a band record in a room in the Hilton hotel, we got some recordings off of that, and I sort of stitched that together as part of the score as well, doing the same thing, which was adding other elements on top. It was very interesting at that point as I'd never studies Ethiopian music, so it was a crash course in the various styles of music that came out of Ethiopia, which is a very fascinating country, it's an ancient Christian civilization, but at the same time it's part of Africa and a more Arabic culture as far as the music goes sometimes.

It also seems there's a similar crash course in I Am Sam. There's the orchestral score, but there's also these little strange musical noises, that almost sound like little wind-up toys. What are those?

It's a mixture of various smaller instruments. I suppose that was literally it – I was using lots of ukuleles and small guitars and string instruments and even childrens pianos! It was an obvious place to go with a character who was a child. I liked the paradox of a child-man who was actually a better parent than the lawyer who was there to supposedly support him. He was more responsible than somebody who we think of as a fully formed adult, so it just gave us some contrast to play with. You could have very small instruments playing and at the same time you added a big string section, and when you added the two things together you could see that it's a metaphor for what you're seeing in the character.

After this you worked on the drama Drumline. Since the film was about the music, it seemed like it had a more privileged role than just a pure underscore. Was this like scoring any other film?

After this you worked on the drama Drumline. Since the film was about the music, it seemed like it had a more privileged role than just a pure underscore. Was this like scoring any other film?I was brought in quite late on in the day on that film. They'd already recorded a lot of the music with the bands down in Atlanta so all that had been done was already being incorporated into the film, so I didn't have much of a role in this. One of the things I did have to do was technically improve some of the sound and some of the recordings. I had a lot of production work to do on that film to make all of the band, in particular the band that wins, we had to make them sound better. We did that with all sorts of techniques such as adding in the earth-wind-fire horn section into their playing and we recorded some of the snare drumming with better microphone techniques. For instance, when you see the bands with the big bass drums going it sounds pretty good when you're there, but the recording didn't just represent the real punch of a lot of the drums, so we added in other drum sounds and samples to the band to make it sound how it looked. It's the tradition of Hollywood to make real life bigger than real life, so that was my job on that, along with the score and making sure that the score flowed in and out of the musical numbers as well.

Now, D-Tox was a really problematic movie. I heard it was shot in 1999 and released 3 years later and I heard you had to do lots of reworking on this score. What happened here?

I honestly can hardly remember that one, it went past very quickly. I didn't actually rework it that much. I did a score for it and as you say, almost a couple of years went past before they released it and I think by that time the movie had been re-cut a lot so they just took a lot of the music and re-organised it and added a few little bass tones and things like that. I've never actually seen the final film of that. I enjoyed working with director Jim Gillespie, he was a great guy, but the film just didn't work and I think everyone knew that and they were trying to put it together and when the film's like that, there's nothing a composer can do. You just do your best work, which I did at the time, and watch it disappear.

How do you know that this is your best work? What tells you that this is the best cue before you present it to the director or producer? Do you have a gut feeling of this?

Sometimes you never know – you absolutely have no idea! If you feel it's supporting and making more vivid the drama that you're seeing, then that's working. If it's working for you but it's not working for the director, it might just be that there's an element of it that is causing some kind of irritation and it's pulling your ear away from the dialogue and the story, or it could be that you're in completely the wrong style and the director always had and idea of it sounding totally different. Hopefully you've talked enough before that point, and experimented. I start out every film by trying a lot of experiments. Sometimes I have an idea when I talk at the beginning of a project, and we say things like "that would be an interesting idea for the music", and other times, whatever I've said hasn't worked out, but I've tried some other things while I've been working on my own and I present them to the director and say "here's an alternative" or "here's a different view, what do you think?" So you go through this constant process of experimentation with the director. All the music I write is all a combination of both my tastes, how I like music, how I like music in film, and in a way, more importantly, how the director or producer, how the filmmakers like music and what they like about the way it works or not. That's why I hope every score I do is going to be different. It's almost written by me and the filmmakers.

You seem very adaptable in that sense. Have you ever been dropped off a project because there was no harmony between you and the filmmakers?

No, not really. I would be if it weren't for the fact that every film I do, I try things and I make mistakes and I make successes and we keep going until every cue is a success.

I'd like to ask about what the listeners want to hear most about – the Bourne scores. How did you get involved in the Jason Bourne films? Were you the first choice for this series?

I'd like to ask about what the listeners want to hear most about – the Bourne scores. How did you get involved in the Jason Bourne films? Were you the first choice for this series?No, ironically of course, the year before I got that job, I was standing in a video store with my agent, we were walking around – I think we were just killing time – and we were looking at the shelves of films and I was pointing out filmmakers that I thought were great, and my agent said "Wouldn't it be great if I could work with this guy and this guy?". I was looking at Go By Doug Liman, and I had just seen it, and I said "This is an incredible film you know, this guy is really good. Could we find out what he is doing at the moment?" And of course the next day she called and she said he's doing this film called The Bourne Identity but they've already got a composer so I didn't think anything of it, but a year later, the film had been delayed and it had gone through a bit of a rough exogenesis. It had been a bit tough for everybody, but that's the way Doug works, and they already had a score and it wasn't working at all and the composer (Carter Burwell) who was doing it was on another project and he didn't have time to re-score it, so that's why I got a call and I spoke to Doug. He was in a taxi in New York and I was at home in Los Angeles and we talked for about an hour on the phone about what music could do and what it shouldn't do and the things people don't try much, and I think he realised that I was quite willing to try lots of things, and I think at that time that's what he needed. So they took me on and I spent a good four weeks just trying completely different types of music against the picture. I knew what they had recorded and I knew it had a full orchestra and it was much more traditional, and I realised that wasnt worth going too close to as they'd tried it once by a very good composer and there was nothing that was going to stick from that so why go there again? So I went for a very electronic score, as modern as I could think, and in the end we introduced some more classic elements to it, quite near the end of the process.

There was a change in the directors between the first two movies. Did this have any effect on your work?

Well, the interesting thing is that everyone said "We like the music of the first movie. We'd like you to bring the same theme to the second one and just let it develop as the film develops." And Paul Greengrass, I didn't know anything about him at the time and I remember buying the DVD of "Bloody Sunday" and being blown away by it, it's such an amazing film, but it had no music in it whatsoever – I could hear a few very low tones but contained almost nothing musically. So I was concerned, I thought this guy's going to come on and he's not going to want any music, but it turned out he actually did and he was very sensitive to the fact that he was walking into something that was already working very well, but he obviously wanted to bring his own sort of touch to it, which he did very much and that's why the series has moved on and became interesting again in it's second version. You had a great character actor in Matt Damon and in Jason Bourne along with the same problems, but seen from a slightly different view. I think the only thing I did was make it a bit more acoustic. I added a bit more orchestra and obviously some ethnic instruments, somewhat appropriate to Goa in India. There were certain elements to that. But other than that the main thing was to try and take what had been established in the first one – the sense of it, the smell of it, and continue it, but keeping it appropriate to the picture that we were making.

Do you know what will happen to the themes in The Bourne Ultimatum, the third picture in the series?

I don't know yet. I've been hired to score the movie and I know that Paul is shooting it, if not now very soon, but I don't know the story yet, and I haven't seen any footage yet. I probably won't work on this until next year, but I'll do with it whatever needs to happen to make the story work. But I should imagine it should still use some of the framework and some of the vibe and essence of it. That would mean utilizing some of the themes from it and perhaps developing them in a different way.

You have some more action movies in your filmography like Agent Cody Banks which has a really James Bondian score. Mr. & Mrs. Smith had this really Hispanic feel to it. How do you find inspiration for these basic templates of the score?

You have some more action movies in your filmography like Agent Cody Banks which has a really James Bondian score. Mr. & Mrs. Smith had this really Hispanic feel to it. How do you find inspiration for these basic templates of the score?With a film like Agent Cody Banks it was just me reliving my childhood a little bit. I love the Bond scores and I've always loved John Barry's music so it's a homage to him, but at the same time, they wanted it to be a more modern film so we took bits of the score and made them more modern. With Mr. & Mrs. Smith part of the Hispanic, or Latino or Spanish flamenco feels were a shorthand to try and really give as much heat to the relationship between the two main characters. It was there to show this passion that these two people had for each other, even though they were trying to kill each other. So it was just a very useful story technique, that's all.

You had a really busy year so far – you've scored four movies already! X-Men: The Last Stand was the biggest budget score of these. Being the third in the series, how did you feel about continuing the series?

I certainly knew the first two films and I liked them very much and I think Bryan Singer is a superb director. The first two movies were scored by two different people and what seemed to happen between one and two was an element that was the same, it was in the same language, and I felt, even though this movie required a unique score, it didn't seem to be making any sense to break the flow from the first two. So we basically picked up the same language, the same family of music and didn't try and reinvent the world for this third film. It had to be in the same genre that had been established but ultimately all the things are unique, they're all new to the film but one theme honours the first two themes. It's like something of an amalgamation of the first two themes with new notes and new intervals, but it sort of has the same infrastructure. I just wanted it to feel like it had a level of familiarity.

You also scored the incredibly dramatic United 93 which is based upon the events of September 11th. How did you choose to score this gritty and really tragic movie?

You also scored the incredibly dramatic United 93 which is based upon the events of September 11th. How did you choose to score this gritty and really tragic movie?Because it was Paul Greengrass, he and I had been talking even last summer about Watchmen. He was preparing to do Watchmen which unfortunately didn't happen, but as soon as he got the green light for United 93 he sent me a treatment, which is like the beginning of a script, however in that film there's no real script, but even from the treatment I could tell it was going to be a very hard film to do. When the footage came in, I was taken aback by the intense drama of it, even though it was just a rough-cut. I talked a lot about whether there should be any music. What was the point of music in a film like this? What should it be for? It ultimately became two questions. We tried to get the music to lead people throughout the film and hold their hand really, and say "come with us, we'll take you through the film, we're getting through it" because it's so harrowing. I almost felt it didn't need any music at all. There were moments when really the music just needed to be a prayer, not literally, but for us all to think about what we're seeing, the story, the people. Hopefully it gives the feeling that we are the same as the people in the film. Paul was almost using the film as a metaphor to how we are in the West – we are given two options, one is to do nothing and one is to fight – and neither succeeded in helping them on the plane. And it seems that neither succeeds helping us in a society, living with people with a different ideology.

Your first and last projects for this year are both ice-themed animations, Ice Age: The Meltdown and Happy Feet. How can you delve into two similar themed projects with different ideas?

The two films couldn't be more different, ironically, except for a lot of snow in them. Ice Age: The Meltdown was the same people I had worked with on Robots. Blue Sky are a wonderful company, and the director and the producers and everybody at Fox as well. I think they enjoyed working on Robots with me, and they just wanted to continue the fun we had with that. We headed into Ice Age: The Meltdown and just had a ball. It's a great bunch of characters that were established in the first movie. It's got great voice and writing talent in it and it's spectacular as well. Some of the great moments of animation are in Scrat, the sabertooth squirrel. He's one of the finest pieces of animation I've ever seen. When it comes to comedy timing, there's nothing better than that. But Happy Feet is a very different film, and I've been working on that for four years now. I was brought on very early by George Miller, the director. He felt he just needed one person to create the score and the song arrangements within the movie because it's almost a musical – he calls it an "accidental musical". There was a lot of work over the four years to put together all of these musical numbers in advance so they could be animated and finished. At the same time we developed the score, which we finished in Australia this summer.

Your fans are really lucky as most of your scores are released on soundtracks, which is not always the case with other composers. In what ways are you involved in the release of the soundtracks? Some composers are really picky and others just leave it to the producers. Where are you on this scale?

Your fans are really lucky as most of your scores are released on soundtracks, which is not always the case with other composers. In what ways are you involved in the release of the soundtracks? Some composers are really picky and others just leave it to the producers. Where are you on this scale?For instance, on Happy Feet I'm the executive producer of the soundtrack album so a lot of the songs on the soundtrack album (which only has one score suite) I produced and arranged and had a very big part of with George Miller. But at the same time, we are releasing a score album, which is basically the remaining music that's in the film and I have a little bit more to do with that in the sense that I edited everything. I spent quite a lot of time editing the scores to try and make them flow as well as they can, and try and make them represent the structure of the movie as best I can, so they sound as close to the experience you get when you watch the film as possible. So if you remember the music from the beginning to the end in the film, that should be what the score album represents. The soundtrack album is slightly different as it includes a song by Prince and the Beach Boys and a few other artists which were in the movie, but in a way that I had no control over and that type of album works very differently. The people who buy it are not really interested in score, they are more interested in the songs of the movie and what they perceive as the musical numbers. So you have to construct it so that the album flows in a different way. It's not about being exactly like the movie in any way. Even though the Prince song, which is a great song he wrote for the film, comes on the end titles of the film, it starts at the beginning and it's a great way to start the album.

In retrospect, if you look at all your scores, which is your best experience, the one you are proudest of, and which you'd like to do a little differently if you had another chance?

Well, I don't know. I enjoy every experience in someway, whether it's just in the making of the music or sometimes actually the collaboration with the filmmakers. On Happy Feet I've just had a great time with George Miller. He's an amazing man and an amazing filmmaker and an amazing educator for me. I think I learnt more on this film than I have learnt on any other film, and I think every film I did while I was working on this film was improved by what the knowledge I was getting from working with George. I think this film will always be special to me because I had such a big part in it and because I learnt so much from it.

Have you ever had a really problematic piece of music that you just couldn't get your head around?

The one I like to tell about Happy Feet was that there was this one piece of music which I wrote very quickly for what we call "the dive from the worlds highest iceberg", and when you see the film you'll understand. I wrote this piece and I liked it very much and George absolutely loved it. It was written about a year and a half ago and it stayed in the film – every time things got changed around, it stayed. It got moved, it never got dropped, and it was a great example of how music for a movie should work. But right at the very end, just before we were starting to record with the orchestra, I said to George, "I need to get some things orchestrated. I need to start a pipeline of orchestration. Are there any cues that we know we like and are going to keep?" and he said "Well I can defiantly tell you that we're using the music from the dive from the tallest iceberg." And that's when a little bell went off in my head. As we talked about it, we suddenly started to play with it a little bit and before we knew it, I tried something completely different, and it was much better. So the piece that I wrote, and stayed there for all those years, the only dead sure thing in the film, actually got chucked out within twenty minutes. It was good, because the piece that's there now is so much better.

What other projects are you going to be working on? We know about The Bourne Ultimatum but is there anything else?

What other projects are you going to be working on? We know about The Bourne Ultimatum but is there anything else?I'm doing some early work on a film called Horton Hears a Who! which is a Dr. Seuss story which is being made by Blue Sky and Fox Animation again. I'm working on that right now because there's some musical numbers that have to be written and recorded before they can begin animating. They're integral parts of the scenes so that's what I'm trying to work on at the moment.

Do you keep in touch with your fans? Do you look on the internet, search for reviews of your scores or do you think it's better not knowing about it?

I try not to. Live by the sword, die by the sword. If you don't like reading bad reviews don't read good reviews. It's really a question of how did the filmmakers feel about what you did and how did the audience that watched that film feel about what you did. I'm not really here to make music for people to listen to, it's for the story ultimately. I try and keep focused on that, but try and make it as musical as I can. I think if I keep doing good work for the film and for the story, I think it will provide people with a good storytelling experience. If it sounds good separated from the movie then that's a bonus for me. I try not to think too much about that because I don't want to be racked up too much in the music I have to make. I have to be part of the team that's making the movie going experience and not get too involved in it as if it's symphonic writing. I think maybe later on in my life, when I've done enough films and everyone's bored of me in Hollywood, I think I'll write some concert music and more operas. I certainly have lots of ideas, but at the moment I have to supply the storytelling with the best thing I can do.

Lastly, you didn't win an award at the World Soundtrack Awards this year, but suppose you were to win one next year, whom would you thank in your speech? Musical influences, colleagues? Who would you thank for getting so far?

I don't know. So many people go into everybody's life. If you think about how twists and turns of fate happen, it's extraordinary the number of people you're involved with. And that includes the people who turn you down – the people who don't like what you do, the people who criticise you. They're significant because they show you what you're missing. I think it's very important to me to listen to other peoples scores and more importantly, lots and lots of other peoples music. You sit and listen to a record of Bruce Springsteen or Bob Seger albums and it's amazing to hear Bruce Springsteen and this band in a house recording these old songs and the amount of emotion they get into them. You suddenly realise that perhaps there's more too music than just manipulating every single aspect of it – cleaning things up and using auto-tune and editing and making sure every recording is perfect and pristine – all their stuff is really rough and raw. I always think I really need to try and look more towards some of the great recordings out there. They would be who I would thank. Every piece of music I've heard in my life I need to thank because it goes in and it gets filtered through your own consciousness and preferences and likes and dislikes. Music still makes me cry, from the first time I hear it. There's certain pieces, and they might be pieces I've never heard before. You don't know why and you don't know how. It's a pre-verbal language and it speaks to us in such a deep way. All I'm trying to do is bring that history of all the music that I've ever heard and I'm trying channel it in a way that helps us tell stories which are the other significant thing about humanity. Humanity is about telling stories to help each other understand. It's like group therapy really! I don't know if there's anyone specific at the moment, but one day I may be able to tell you!

To know more about John Powell's work, please visit the composer's official website.

Photograph from: John Powell, Tom Kidd

Special thanks to Tom Kidd

November 26th, 2006

Special thanks to Tom Kidd

November 26th, 2006